CS 467 - Steering Behavior

Due: 2020-04-13 5:00p

Goals

- Learn one approach to implementing steering behavior

Prerequisites

- Accept the assignment on our Github Classroom.

- Download the git repository to your local computer.

Assignment

For this practical, we are are going to implement the seek and flee actions. The seek action is explained in a fair amount of detail in The Nature of Code, but there is some value in working through it yourself and playing around with it.

Starter code

Spend a few minutes looking over the starter code before you begin. While I renamed the class Agent, much of the code remains from our Ball class from earlier. You can see that we retained the relationship between position, velocity, acceleration, and force. The Agent class has also retained its applyForce function, which should be our primary function for actually moving the agent around. The only real change is the removal of mass as the forces we will be generating would compensate for the object's mass anyway.

I have also left in the code to update and draw the agent. To draw the agent, I borrowed the code from our rocket ship so that we can see the direction the agent is facing. The assumption is that the agent is always moving forward, so we use the vector of its velocity to determine the heading.

Part 1: Add a seek function

Add a new function to the Agent class called seek(target). The target parameter will be a p5.Vector object holding the position of the target we want the agent to run to.

Our implementation of seek will start with the same structure as Shiffman's.

First, get the desired vector by subtracting this.position from target (remember to use the static version to avoid changing target).

Of course, this vector is probably too large, and would teleport the agent to the target. We want the agent to move towards the target as fast as it can, but not instantaneously. This means we need to set how fast the agent can move. In the constructor, add a new property to the class called maxSpeed and set it to 3.

To get the agent to move in the desired direction at its top speed, start by normalizing the vector (normalize()). This time, use the vector's instance method. We can update the vector in place since we don't need to hold on to the old one. This gives us a unit vector -- a vector that points in the right direction (towards the target) but only has a magnitude of 1. Multiply this by the agent's max speed to get the "desired velocity".

Now it is time to calculate the steering force. Recall that .

Use the agent's current velocity to computer the steering force.

Finally, call the agent's applyForce and pass it the steering force.

To test this, add a line to the main draw function that tells the agent to seek the mouse (agent.seek(createVector(mouseX, mouseY))).

Try varying the max speed and observing the behavior.

Part 2: Add a force limit

As described in the lecture and the reading, the current version of seek allows the agent to turn on a dime. If the move the mouse, the agent will instantly align wth it.

In the agent's constructor, add another instance variable called maxForce. We will use this to limit how quickly the agent can come about. Set it to 0.1.

In the seek() function, use the limit function available on vector objects to cap the steering force to maxForce.

Run the code again. The agent should now curve around when asked to make extreme course changes.

Play with this value to see how larger and smaller values affect the behavior characteristics of the agent.

Part 3: Brake gently

As Shiffman observed, in the current configuration, your agent will run at full speed until it hits the target (at which point it has probably overshot and has to come back). A more natural behavior is for the agent to slow down as it approaches the target.

To implement this, we imagine a circle around the target. When the agent is inside the circle, it will reduce its speed proportional to the distance from the target. Outside, it will still run full speed.

The radius of this circle essentially set the stopping distance of the agent, and is another parameter we could use to vary the characteristics of individual agents. However, we will fix it at a radius of 100.

There are a variety of ways that you could implement this, but I'll give you a fairly efficient one. Computationally, the biggest problem we have is determining the distance away from the target. This operation is a bit expensive since it requires a square root to calculate (Pythagoras again...). In this instance, we can get away with the square of the distance (the behavior will be slightly different, but not very). We can get the distance squared very easily with the magSq method of the first vector we computed in the seek() function.

To change the speed based on the distance squared, I suggest using the map function to convert between ranges. Because we are using the square of the distance, the range for the distance will be from 0 to 10,000, while the range for the speed will obviously be 0 to the max speed. If you pass this the square of the distance, it will give you actual speed... almost.

Because of the way map works, if the agent is farther away from target than 100, the computed speed will be larger than the max speed. Fortunately, we have the constrain() function for instances like this. So, compute the new speed using map, and then constrain it to fall between 0 and the agent's max speed with constrain.

The agent will now slide to a stop at the target.

To see this effect better, draw a circle around the mouse with a radius of 100. When the agent crosses the border, you should see it slow down.

Part 4: Wrap around

A curious part of our setup is that the space is wrapped, but the agent will go the long way across the center of the canvas, even if it is quicker to shoot over the edge.

We are going to implement this by tweaking the initial vector pointing at the target to point in the opposite direction if it is shorter.

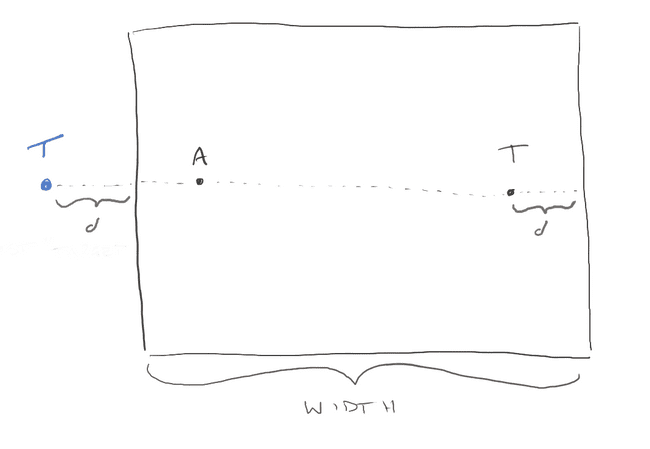

We can actually do this component-wise, so let's just consider the x dimension. If the magnitude of the x component of the vector (i.e., the distance between the agent and the target in the x dimension) is larger than half of the width, we know that it would be shorter to go in the opposite direction and take the wrap-around. We can check this by looking at the absolute value of the x component.

The question is now 'what should the new x component be?'. Consider the case when the x position of the agent is less than the x position of the target and the distance between them is larger than half the canvas width. If we want the agent to aim at the target in the opposite direction, we need to imagine the target shifted from its current position on the right of the agent to a new location on the left. We can do this by subtracting width from the target's position.

Since subtraction is commutative, we can apply this subtraction to the vector after the initial vector subtraction.

If, on the other hand, the target is on the left and the agent is on the right, now we want to add width to the position of the target.

So, we start normally by subtracting the agent's location from the target. Then, we check if the absolute value of the x component of the resulting vector is greater than width/2. If it is, then we either add or subtract width from the x component depending on where the target is (which we can tell by looking at the sign of the x component of the vector).

The y dimension works exactly the same way.

Test this out. You should see the agent now taking the optimal path.

Part 5: Flee

Implement a new action on your agent called flee.

In truth, flee is just the inverse of seek. You can get a basic *flee behavior by copying the seek function and switching the desired vector from p5.Vector.sub(target, this.position) to p5.Vector.sub(this.position, target).

Try this out. In the main draw function, call agent.flee(createVector(width/2, height/2)) to make the agent fear the center.

This time, let's make the effect more localized. Add a line that checks if the square of the distance between the target and the agent is greater than 10,000 (i.e., the distance is great than 100). If it is, just return without applying any forces.

Another thing you could do is to remove the limiter on the steering force, so the agent really steers away from the center of the screen.

Part 6: Make a fleet

Use the same technique we have used before to supersize the sketch. Replace the single agent with an array of agents, placing them randomly throughout the space. Give the agents different characteristics by randomizing their speeds and max force.

There are lot to ways to play with this. For example, you could have random food drops that are consumed by the first agent to reach them. You could have them run away from the mouse, maybe only if the mouse button is clicked.

Finishing up

Commit your changes to git and push them back up to GitHub. I will find them there.